Installation view of “Prayer and Transcendence” at the George Washington University Museum and Textile Museum. (Cara Taylor / George Washington University)

“Oriental rugs,” as they are often called, have been appreciated for centuries for their beauty and artistry. Some serve a purpose that’s more than mere decoration for a floor or wall, however. “Prayer and Transcendence,” an exhibition at the George Washington University Museum and Textile Museum, focuses on Islamic prayer carpets, showing how they share specific iconography that forms a common visual language across Muslim cultures, while also allowing for a diversity of styles and interpretations.

“[Carpets] are beautiful objects, but they have meanings,” says curator Sumru Belger Krody. “And if you’re not from that culture or religion, it’s harder to read them. This exhibition tells you how to read that meaning.”

The exhibition is a feast for the eyes, showcasing 20 carpets dating from the 16th to 19th centuries and spanning lands from modern-day Turkey and Iran through the Caucasus and Central Asia and into the Indian subcontinent. More than half are Textile Museum holdings, with the remainder on loan from four other collections.

The central element of Islamic prayer carpets is their directionality: Each features an archway around which the rest of the design is composed. When laid on the ground with the arch oriented in the direction of Mecca, the textile physically delineates an area for prayer. The rugs may also be hung on walls to denote a space for worship.

Torah ark curtain (early 17th century) from the Ottoman Empire in Cairo. (George Washington University Museum and Textile Museum/Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1915)

A prayer carpet (1890-1910) from the Caucasus. (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum/Gift of Elizabeth Gowing, Harborne W. Stuart, Peggy Coolidge, and the estate of W.I. Stuart in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Willoughby H. Stuart Jr.)

Among the most gorgeous works on display are those with imagery of gardens, representing paradise. A stunning piece from 18th-century Kashmir is a riot of colors and patterns, featuring a scalloped, curved archway flanked by cypress trees with a millefleurs field of assorted flowers in the center, all surrounded by a more stylized floral border pattern. It was also made with especially rich materials: a combination of silk, cotton, and pashmina wool.

“In the Quran, paradise is described in several sections as this big, luscious garden with flowers, greenery, waters. … If you live a pious life, you can enter,” Krody says. “These carpets kind of in miniature give you a glimpse of what [the afterlife] may be if you do the right thing.”

On the walls, lines from the Quran and photos of mosques in countries from which the rugs originate help add religious and cultural context.

The carpets range from an exquisite piece dating to 16th-century Iran that was made with silk, wool and metallic-wrapped thread by weavers employed by the Safavid shah’s court to simpler rugs created by rural women for household use. One particularly vibrant example from the Caucasus has a pattern of stylized, almost hexagonal paisleys in an array of colors.

A late-18th-century saf (multi-arch prayer carpet) from Warangal in India’s Deccan Plateau. (George Washington University Museum and Textile Museum/Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1950)

“The designs are created for [court] use, but then kind of go down the echelons and reach the masses, being imitated in various different ways,” Krody explains. Although styles reflect local preferences, they were also influenced by available materials: Rural artisans usually worked with wool that wasn’t nearly as fine as the silk often used by court weavers, leading to designs that were more geometric and considerably less intricate.

Lamps, clearly modeled on the types of lights that traditionally hang in mosques, are another important motif, symbolizing divine light. Here the museum provides a fascinating counterpoint to the prayer rugs through the inclusion of two carpets woven in the Ottoman Empire and used, rather atypically, in synagogues as parochets, or Torah ark covers, showing the degree of mutual influence between the empire’s Muslim and Jewish communities.

One of the ark covers hangs next to an Ottoman prayer carpet with such similar design and iconography — a central archway with a lamp or flowers hanging from it; concentric patterned floral borders — that it would be easy to interchange them were it not for the Hebrew inscription at the top of the parochet.

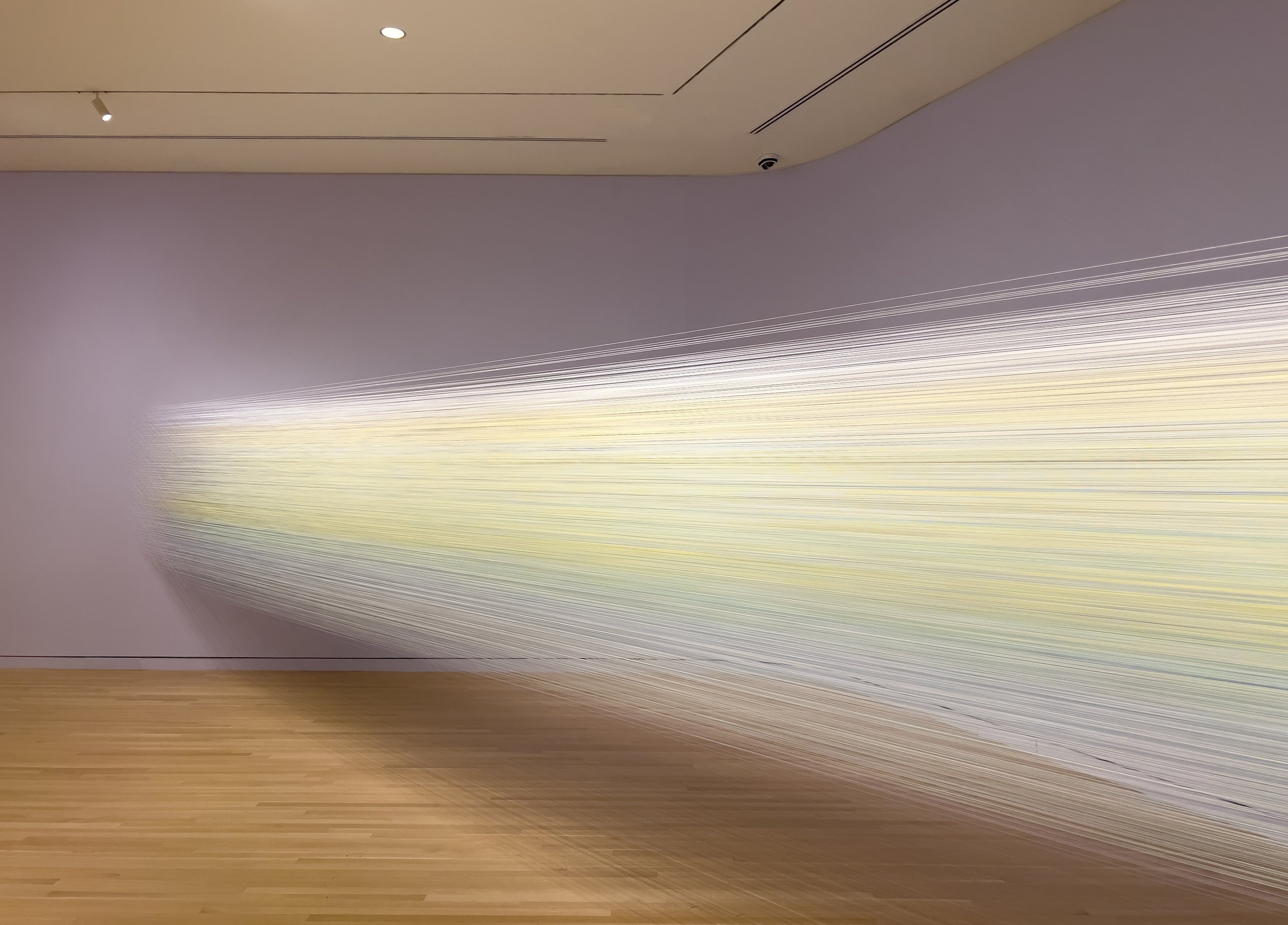

Installation view of Anne Lindberg’s “What Color Is Divine Light?” (Derek Porter)

Just upstairs from the carpets, a site-specific installation by contemporary American artist Anne Lindberg, “What Color Is Divine Light?,” continues the theme.

Lindberg’s luminous work evokes a sense of wonder. At first glance, it seems like an illusion created from something intangible, such as beams of light. In fact, it was made with thousands of fine cotton threads on a color spectrum between yellow and blue, stretched tautly between two lavender walls and lit so that the work appears almost psychedelic, vibrating from close-up.

The installation aims to create what scientists call “impossible colors” — imperceptible to the eye and brain — between the hues of the threads. In grappling with the impossibility of depicting the divine in physical form, the artist is responding to an unanswerable question posed in an eponymous 1971 essay by art historian Patrik Reutersward.

“What Color Is Divine Light?” invites contemplation; the museum is also holding several interfaith and performance programs and encouraging quiet reflection in the space. On a recent Saturday, several Muslim women attending an Islamic calligraphy workshop held in conjunction with the carpet exhibition rolled out yoga mats that were on hand and performed afternoon prayers.

Not only visually stimulating, the juxtaposition of Lindberg’s installation with the Islamic prayer carpets, along with the Torah ark covers, makes a wonderful case for the idea that the divine can be found in many forms.

Installation view of Anne Lindberg’s “What Color Is Divine Light?” (Cara Taylor / George Washington University)

Installation view of Anne Lindberg’s “What Color Is Divine Light?” (Derek Porter)